If NHS data analysts were to draft an American Declaration of Independence-style manifesto, then one of the truths we hold to be self-evident would be that all information should be useful. Our data shouldn't just be something that managers and clinicians find "interesting". And it certainly shouldn't just be something they ignore. No. Our data should be instrumental in helping to change things that need to be changed.

But the process by which information gets turned into action (Before he started using the hashtag #showflow, Chris Green used to add the hashtag #dataintoaction to his tweets) is not at all straightforward. This engagement between data and decision-making is the Holy Grail for a lot of us, and we spend a lot of time trial-and-error-ing different ways of achieving this alchemy.

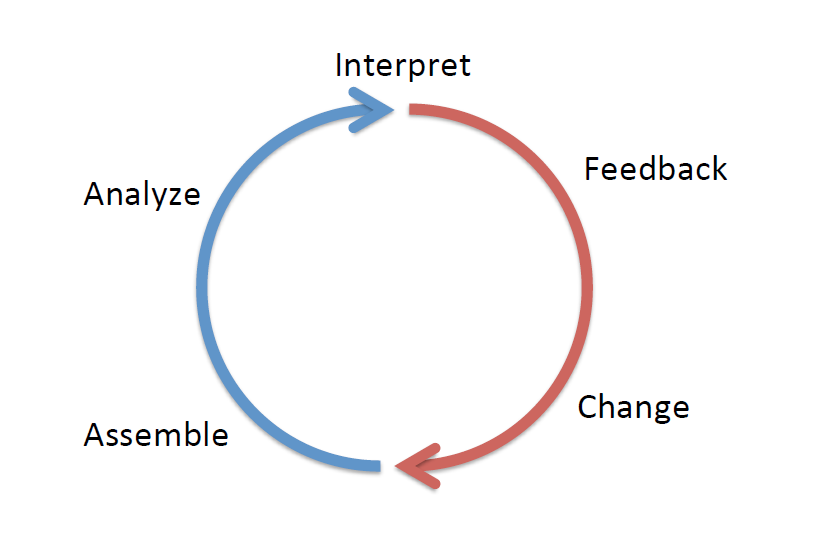

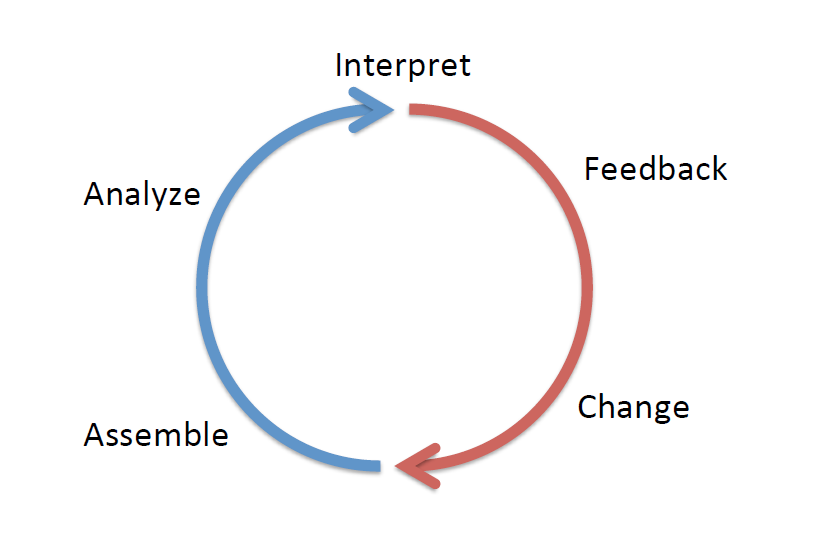

One theory I stumbled across recently is the Learning Healthcare System. This approach by Charles Friedman makes the point that there are behavioural as well as technical aspects to getting data into the bloodstream of the decision-making process. I've re-printed the main diagram below and you'll see that the Learning Healthcare System can be described using five verbs placed around a circle:

The idea is you start at the bottom-left of the circle (if this were a clock, you'd begin at about twenty-five-to-the-hour) by assembling the data. Then you analyse it. Then you interpret the data. Then you feedback your findings to the people who make the decisions that lead to change. Easy.

I very much like the circle-simplicity of this diagram. But I have three things I want to say about it.

Firstly, feedback is important. There are only five verbs in this diagram and feedback is one of them so let's take an overly quantitative—but quintessentially analyst-esque—position and assume that it's roughly 20% of the challenge. We have to publish our stuff, we have to show and tell, we have to get the data messages across to the people who need them. But I worry that we don't pay enough attention to the feedback stage of the cycle. Once we've done our analysis we often just email the Excel spreadsheet to people. We hardly ever feedback our findings in a setting that involves us being in the same room as the recipients. So the end result is that we analysts tend to see feedback as a technical verb instead of the behavioural verb that it actually is.

Feedback wasn't the only verb in that diagram that bothered me; I had issues with assemble, too. Specifically, it irked me that assemble was situated entirely within the blue (technical) half of the circle diagram. I don't think assemble is a purely technical task. I think it has a strong behavioural element. Like feedback, it involves observation and conversations: human-centred and human-facing activities that don't necessarily involve a computer.

The location of the word interpret in the diagram is better: it is at the join between the blue (afferent) side and the red (efferent) side, which is where I think it should be, because it implies—I think correctly—that analysts need help from managers and clinicians interpreting the data. But if interpret can be at the top (twelve o'clock) join, why can't assemble be at the bottom (six o'clock) join? Placing those two verbs at the joins would imply that both activities were collaborative efforts. And that would leave just analyse as the only verb in the purely-blue part of the circle. Which I think is about right.

I said earlier that I stumbled across the Learning Healthcare System theory. I was referred to it by a link in a piece by the Health Foundation's Director of Data Analytics, Adam Steventon, And I'd been led there by the recent blogpost on healthcare analytical capability by Martin Bardsley, who—amongst other things—said:

And I think the key to this is that we absolutely have to understand the behavioural aspects to the things that we do. In particular, the working out what data we need to analyse (assemble) and the working out how to disseminate the findings of our analysis (feedback). We need to question the orthodoxy that assemble and feedback are technical activities. In my view, they are not, they are behavioural, and they need to be done collaboratively with our users. Our focus on analyst training should probably be focused on those areas too: how to get analysts to connect better with managers and clinicians.