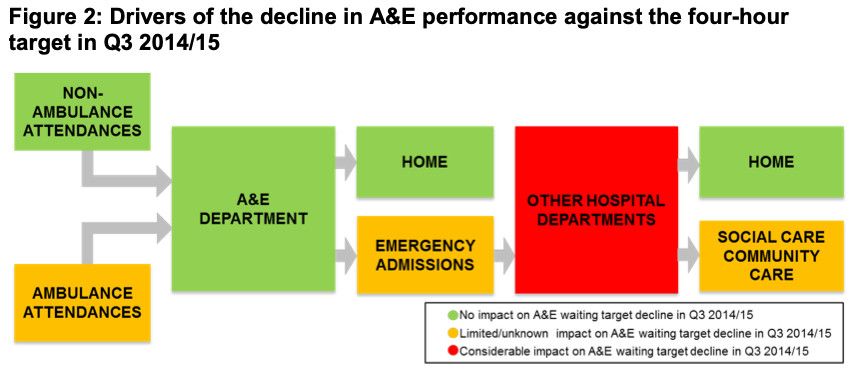

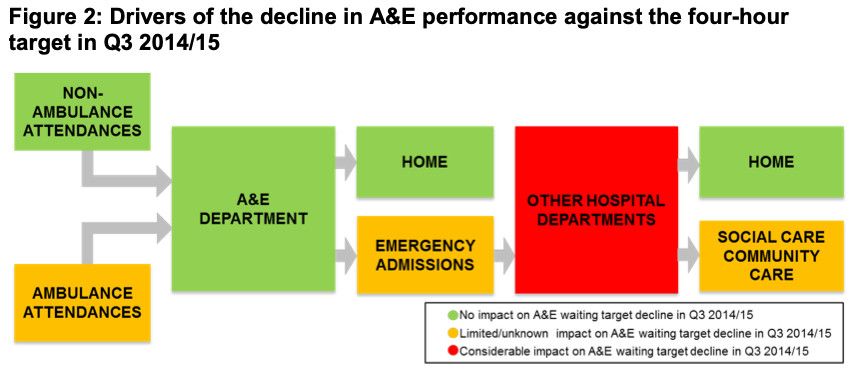

This is a patient flow diagram produced by Monitor (NHS England's regulatory body) back in 2014:

The boxes represent the various departments or staging posts that patients pass through during patient flow journeys, and the colour of the boxes is designed to represent the impact each box has on patient flow. The box with the most impact on patient flow—the red box—is the one labelled "OTHER HOSPITAL DEPARTMENTS", which mainly consists of the inpatient wards in the hospital.

In a typical general hospital, these wards are usually organised into clinical directorates, and each directorate will have a bed allocation. In theory, the specialties are supposed to live within their bed allocations. But in reality, a lot of borrowing and lending of beds takes place in general hospitals. Medical specialties tend to borrow; surgical specialties tend to lend. Borrowing and lending often takes place within the medical umbrella, too: it's often the case that specialties like General Medicine and Medicine of the Elderly will borrow beds from other medical specialties like Cardiology and Gastroenterology.

So yes, there's a lot of borrowing and lending. But there's another problem, too, which is that the beds as a whole are nearly always full. Which means that there are nearly always delays whenever a patient needs to be admitted to one of these beds. These delays can be very, very long. Not just hours long, but days long.

So yes, in that diagram the red box is right to be there and it's right to be red. And you'll struggle to find anyone in the NHS that disagrees with either the right-ness or the red-ness of it.

But the problem is that nobody seems to be able to do anything about it.

Why the inaction?

Here are three reasons. There are probably more, but let's get these three out into the open for starters.

The first reason for the inaction is that the red box is at least one step removed from where the patient flow problems manifest themselves in the most 'public' way, which is in the crowded Emergency Department (ED). The NHS seems to have difficulty—both organisationally and culturally—with problems that are located remotely from their causes, so if you go to bed meetings you'll see lots of information about the ED and how full the beds are, but not quite so much information about what's been happening in the inpatient wards to cause the beds to be so full.

There's a related problem here, which is that the NHS tends to be fixated on the 'here-and-now', whereas the bed fullness and overflow problems we're witnessing today have been created by events that have already happened (the 'there-and-then'). If Respiratory Medicine beds are overflowing by—say—eight beds and encroaching into the bed allocations of General Surgery and Orthopaedics, then that overflow and encroachment is the result of inpatient stays that began days, weeks ago: the 'there-and-then' matters a lot if we're to understand why the 'here-and-now' is so suboptimal. In fact, it's probably best to understand the 'here-and-now' as a result of patterns of behaviour that have occurred—and continue to occur—in the downstream specialties.

The second reason why the red box is left unaddressed is that providing meaningful patient flow information to the clinical directorates isn't quite as straightforward as it might seem. If you want to provide Respiratory Medicine (for example) with data on the inpatient activity that is supposed to fit into its bed allocation of—say—24 beds, then data analysts need to do quite a bit of data-wrangling work first. They have to exclude time spent by Respiratory patients in the Acute Medical Unit. They have to exclude time spent in the discharge lounge. They need to have a discussion about whether to include or exclude time spent in critical care wards (and the answer to this question will vary from specialty to specialty; Respiratory Medicine may say 'exclude' but Cardiology may well say 'include'). There will be decisions to be made about the time patients spend in day case or short stay areas (and I can speak from bitter experience that it can be tricky to separate out the activity that is supposed to be there from the activity that is not supposed to be there). These inclusion/exclusion decisions require quite a bit of SQL-style technical know-how, and quite a bit of knowledge of the way the data is stored and classified. But the big problem here is that these decisions also require the data analysts to have quite a bit of on-the-ground 'domain knowledge'. And NHS data analysts are famously and stereotypically remote from the coalface, not known for their levels of engagement with clinicians and service managers so that they can find out which wards and patients to include and exclude.

The third reason for inaction is pretty much irrelevant if we can't overcome the first and second reasons, but let's assume for the moment that we can. Let's assume that we've persuaded the powers-that-be at the hospital to provide information for the inpatient specialty directorates. And let's assume that the analysts have sliced and diced that data in the right way so that it's measuring the right things. We've still got this third hurdle to jump, and that is that we somehow have to make the information actionable.

There are at least a couple of things that need to happen in order to make the information actionable. One is that we've got to find ways of visualizing the data on admissions, transfers, length of stay and bed occupancy so that it's recognisable and meaningful to each directorate. Clinicians have got to be able to recognise their workplace when they look at the data, so it might be the case that standard off-the-shelf data visualizations won't cut it. So we'll probably need to do a bit more fieldwork and experimenting to see what visualizations work and what visualizations don't work.

But actionability also means that we have to find a way of getting this information into the bloodstream. This 'there-and-then' data needs to be pored over and discussed by the clinicians. Possibilities need to be aired. Further detail will need to be requested. So it's likely that this dissemination will need to be carried out in face-to-face meetings and not just relegated to some hard-to-find, self-serve dashboard. The information will need to be a living, breathing thing. It might take a few iterations—a few monthly meetings—for it to become an agreed, fit-for-purpose dataset for ongoing monitoring by each clinical directorate.

These reasons for not addressing the patient flow issues within the red box seem daunting: a formidable combination of technical, behavioural and cultural barriers. But they are by no means insurmountable. Patients are dying as a result of poor patient flow. We need to get started on this work immediately. Operation Red Box, anyone?

[31 January 2025]