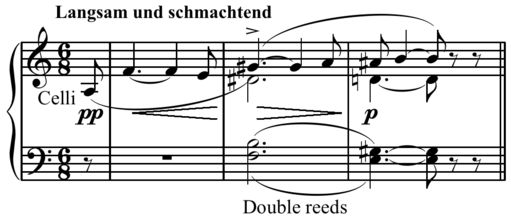

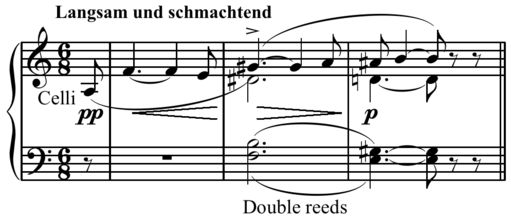

I was teaching Arguing with Numbers to a group of NHS data analysts in London on Monday and I decided to start with a slide with some music on it:

And my question was this: “Is this what data looks like to people who don’t ‘do’ data?”

It can be difficult for data analysts to imagine how daunting, how intimidating, how forbidding data can appear to people who aren’t accustomed to data. So I was searching for an analogy that might help analysts make this leap of imagination. And I took the gamble that hardly any of the assembled analysts would be able to read music—or at least read music fluently—in order to be able to ‘hear’ the music in the excerpt.

And the analogy seemed to work! I projected this musical phrase onto the screen and said something like “Well, I think we can all agree that this really just speaks for itself!”, and of course it didn’t speak for itself at all, it was just impenetrable.

This got us talking about how what we think of as just ordinary tables and graphs are actually seen as difficult things to most non-analysts, and we started wondering what things we do as data analysts to make our end product as un-daunting, as un-intimidating, as un-forbidding as possible. And the general consensus was that we try to format our tables and graphs so that they are as appealing as possible. Which is actually just a euphemistic way of saying that we’re trying to make them a bit less un-appealing than they essentially are. Let's face it, there is only so much you can do to a table or a graph to make it more appealing, because when all’s said and done, it’s still a table or a graph and if it’s the table-ness or graph-ness of it that’s making it so un-appealing then we’re really fighting a losing battle here.

Data—in pretty much whatever form it takes—carries baggage. Baggage that's too heavy, too large and too difficult to carry. If you follow Daniel Kahneman’s ideas on "System 1" and "System 2" thinking, then you’ll conclude that the baggage is so heavy it’s actually un-carry-able. Data represents hard intellectual work, the kind of work that human beings run a mile from. (Analysts don’t see it as hard work in the same way as non-analysts because we’re just so used to creating and looking at data – so for us it’s moved from "System 2" to "System 1", a bit like driving or language does once you've learned and practiced it). So unless you can disguise tables and graphs so well that they are utterly unrecognisable as tables and graphs, then this is a lost cause.

There’s a danger with this line of argument that it can all get very depressing very quickly. In many ways, tables and graphs are our end product: they are the whole point of what we—as data analysts—do. And the inescapable fact is that the default setting for the people we’re aiming our end product at is that they have a natural antipathy towards it. Or, to put it another way, the thing we do, people don’t want it.

So we need to find a way out of this. And I think the way out is by separating data's form from its function. Designers are fond of quoting the mantra “form follows function”, by which they mean that the way a designed object looks or feels should be governed by its purpose. Design isn’t about making something look nice; it’s about making something work well. But obviously if you can make it look nice and make it work well at the same time, then you’ve got yourself a winning formula. The trouble is, when we invented tables and graphs as a way of providing form to data’s function, we got ourselves a losing formula. We ended up with something that looked really unappealing to the people who need to be able to use it. A friend of mine once said it was as if data’s form actually inhibited its content.

In my attempts to escape this downward spiral of depressing-ness, I sometimes recall the Henry Ford quote about how if he’d asked people in the 1890s what they wanted, they would have asked for faster horses. This quote (Ford never said it, incidentally, and I don’t think we know who did say it, but it doesn’t matter) is an alluring idea because it creates the possibility that we won’t have to put up with these sub-optimal data vehicles forever. At some point, just as horses were superseded by motor cars, so, tables and graphs will be superseded by—well—something else, something we can’t describe, something that hasn’t been invented yet.

Or maybe it has been invented but it’s been invented in some other, unconnected professional sphere, or the person that invented it doesn’t know what to do with it, they haven’t realised it can be used for communicating data.

There’s a stimulating talk by the writer Robin Sloan in which he references how when Thomas Edison invented moving pictures in 1894 he didn’t really know what to do with them. The first movie ever made (Fred Ott’s Sneeze) wasn’t some proto-vision of what would later be done by the likes of Charlie Chaplin, Orson Welles and Steven Spielberg. No, it was just a technology that had been invented because it could be, and it was only years later that it got ‘appropriated’ by a breed of people that we eventually leaned to call filmmakers.

And maybe this is what will happen to data. Robin Sloan uses the term “media inventor” which he defines as:

Someone who is primarily interested in content (words, pictures, ideas) who also experiments with new tools and new formats. Basically, media inventors aren’t satisfied with the formats available to them by default–. Novel, novella, or short story? Album, EP, or single? Media inventors imagine more. They imagine different. Media inventors feel compelled to make the content and the container.

I think that if we separate out data content from the data container (looked at this way, the data message is the content, whereas tables and graphs are the media containers—suboptimal media containers as it turns out—and we are on the lookout for better media containers. So: not nicer tables and graphs (faster horses) but instead a new, yet to be invented, media container (the motor car).

But what do we do while we wait for this new media container to be invented or discovered or adapted? Do we carry on trying to turn our sow’s ear tables and graphs into nicely-formatted silk purses? Do we try to educate non-analysts to understand our tables and graphs better? Or do we instead experiment with other ways of communicating data?

The man I often refer to as ‘the patron saint of data presentation’—Hans Rosling—used non-standard ways of presenting data as if it came naturally to him. He often behaved as if conventional tables and graphs were an orthodoxy to be dispensed with. So when he described—for example—the changing relationship between fertility rates and life expectancy using a massive animated bubble plot, it just seemed to be the obvious choice of media container. And when he explained the underlying dynamics of global population growth using pieces of Lego on his desk, it's as if we can't possibly imagine a better tool for the job.

But for us lesser mortals it’s difficult. The NHS is a small c conservative organisation, with a small c conservative culture. It is sceptical about innovation if the innovation is seen as being even a little a bit outré. Moreover, to make things even harder, we analysts are a diffident bunch, and most of us don’t possess the self-confidence needed to experiment with new and daring methods of presenting data.

But I don't think it should stop us from trying. It's certainly not stopped me from trying, as I wander up and down the training rooms of the NHS with portfolio case full of A2-sized mounting boards, about 2,000 business-card sized cards and some red hotels stolen from Monopoly sets in order to show how patient flow works.

I hadn’t thought of Flowopoly as a ‘new media container’ when Michael Fox and I ‘invented’ it four years ago, but it seems to draw people into discussions about patient flow in a way that conventional tables and graphs don’t.

[2 March 2018]